Topic index: A

B C

D E

F G

H I

J K

L M

N O

P R

S T

U V

W X

Z

Procedures Treatments

Home

E

Ecthyma | Eczema

or dermatitis | Elastosis perforans

serpiginosus | Ephelides | Epidermal

naevi | Epidermolysis bullosa

| Erythema multiforme | Erythema nodosum | Erythrasma

| Erythroderma

and exfoliative dermatitis | Eye bags

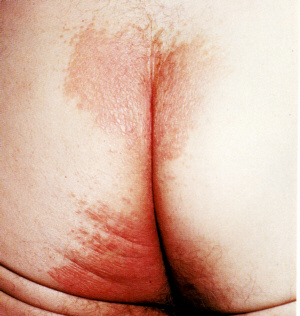

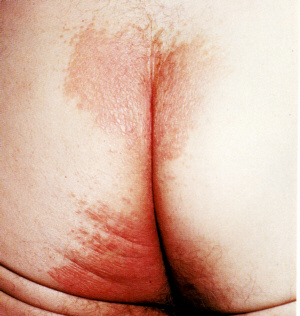

ECTHYMA

Ecthyma is a deep ulcerative

form of impetigo.

It can affect people of all ages but is more common in children,

elderly people and people with diabetes or who are immunocompromised

from disease or medication.

Cause

- Deep ulcerative form of impetigo caused by the streptococcal

and/or staphylococcal bacteria.

- Poor hygiene and malnutrition

may play a role.

Risk factors

- People with diabetes or who

are immunocompromised from disease or medication.

- Infection may follow an insect

bite or some minor skin trauma, including scratching.

- High temperature and humidity,

eg tropical places.

- Impetigo

- Symptoms

- A pustule (pushead) or blister

that rapidly enlarges, ulcerates and then developes a thick adherent

crust.

- Removal of the crust, which

can be difficult, leaves a deep punched out ulcer with a red

border.

- There may be associated lymphangitis

(red lines spreading upwards) and swollen lymph glands draining

the area.

- It usually affects the buttocks

and lower limbs.

- Pain.

- Heal within 6 - 8 weeks, often

leaving scars.

- Ecthyma gangrenosum is a less

common and serious form of ecthyma most commonly caused by the

pseudomonas bacteria. It usually occurs in patients who are critically

ill and immunocompromised. The characteristic lesion of ecthyma

gangrenosum a haemorrhagic (bloody) pustule that rapidly evolve

into a black gangrenous ulcer with a black/gray scab surrounded

by a red halo in as little as 12 hours. Ecthyma gangrenosum may

appear at any site but mainly affects the anogenital area and

armpits. The risk of septicaemia is very high so immediate hospitalisation

is necessary.

|

Ecthyma.

Click on

image for larger view |

- Complications

- Depressed oval or coin-shaped

scars often remain after ecthyma heals.

- In children. glomerulonephritis

(kidney inflammation) can result from streptococcal infection.

- Blood borne spread (septicaemia)

may develop in patuients who are immunosupprressed.

Diagnosis

- Skin swab for bacterial culture and sensitivity tests.

What you can do

- You should consult a doctor.

- Apply warm compresses

followed by removal of crusts.

- Clean with an antiseptic lotion

and apply a thin layer of the topical antibiotic prescribed by

the doctor.

- Observe careful personal hygiene.

- Do not share personal items

such as towels, shaving brushes and blades.

- Separate bed linens, towels,

etc., and boil separately.

- Advice should be given to

patients to avoid scratching itchy lesions. Keep fingernails short especially if you have

an itchy skin condtition such as eczema.

- Avoiding insects through use

of nets and repellent sprays.

What the doctor may do

- Prescribe oral and topical

antibiotics.

- Take a culture to help chose

the best antibiotic to use.

TOP

ECZEMA OR DERMATITIS

Eczema or dermatitis refers

to an inflammation of the skin characterised by redness, swelling,

weeping and scaling. It is usually itchy and constant scratching

leads to lichenification (leathery thickening of the skin). Doctors

divide eczemas into two broad groups:

Exogenous (exo means

external and gen means production in Greek) eczemas are

caused by external factors such as allergy to cement and plaster

or irritation from chemicals, soaps and detergents (see contact

dermatitis). Endogenous (endo means internal) eczemas,

on the other hand has to do with the skin's make-up or constitution.

Hence, they are also called constitutional eczemas. Endogenous

or constitutional eczemas cannot be cured whereas exogenous eczemas

can be if the causal substance can be avoided.

Symptoms

- Acute

eczema (or dermatitis) - red papules, red swollen, blistered,

crusted or excoriated skin.

- Chronic eczema (or dermatitis)

refers to a longstanding irritable area. It is dry, scaly, lichenified

(thick leathery often darkened) skin from chronic scratching.

- An in-between state is known

as subacute eczema.

- Itching is common to all stages

of eczema.

|

Stages |

Characteristics |

|

Acute |

Blisters, weeping, papules (pimply

bumps), pustules (pusheads) |

|

Subacute |

Redness, scaling, glistening serum

and crusting. |

|

Chronic |

Dryness, redness, scaling, lichenification

(leathery thickening of the skin with accentuation of the skin

markings) and fissuring (cracking) |

|

Acute eczema.

Click on

image for larger view |

- Complications

- Complications

- Spread of eczema to other

areas of skin (autoeczematisation) or the entire body (see erythroderma).

- Secondary bacterial infection.

-

- Treatment

- See under specific types of

eczema.

TOP

Ectodermal dysplasia

(ED)

Ectodermal dysplasia

(ED) refers to a group of genetic disorders characterised by defects

in the hair, nails, teeth, skin, nails and sweat gland function.

Other tissues of ectodermal origin, such as the ears, eyes, lips,

mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, throat and central nervous

system, may be affected as well. The ectoderm is the outermost

layer of cells that forms the tissues mentioned above during feotal

life. All ectodermal dysplasias are present from birth and are

non-progressive. Dysplasia literally means “abnormal tissue

growth.”

Cause

Most cases are inherited although less common, EB occurs

without a family history, in which case it is due to spontaneous

mutation.

ED is caused by mutation or deletion of certain genes.

The different types of ectodermal

dysplasia are caused by the mutation or deletion of certain genes

located on different chromosomes. Because ectodermal dysplasias

are caused by a genetic defect they may be inherited or passed

on down the family line. In some cases, they can occur in people

without a family history of the condition, in which case a spontaneous

mutation has occurred.

The combination of physical

features a person has and the way in which it is inherited determines

if it is an ectodermal dysplasia. For example, hypohidrotic ectodermal

dysplasia affects the hair, teeth and sweat glands while Clouston

syndrome affects the hair and nails.

More than 180 different types

of ectodermal dysplasias exist. Yet, most types share some common

symptoms, ranging from mild to severe. The early diagnosis of

a specific type will help identify which combination of symptoms

the person has or will have.

Types

More than 180 subgroups have been described based on the presence

or absence of the four primary ectodermal dysplasia (ED) defects:The

180+ ectodermal dysplasias are recognized and named based on the

specific combination of symptoms shown in affected individuals.

The pattern of these features is important when a physician tries

to make a formal diagnosis.

The following are the most common types of ectodermal dysplasia

but it has to be said theat the largest group is diagnosed as

just Ectodermal Dysplasia, type unspecified.

Hypohidrotic (anhidrotic) ED

(HED) - inherited in one of three patterns: X-linked recessive,

autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant.

Ectrodactyly-Ectodermal Dysplasia-Clefting Syndrome (EEC) - Mutation

in the TP63 gene on chromosome 3q28. Autosomal dominant

Clouston syndrome - Also called hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

because affected individuals sweat normally and exhibit no heat

intolerance. Autosomal dominant disorder.

Ankyloblepharon (fused eyelids) Ectodermal Dysplasia Clefting

(AEC Syndrome) - also known as Rapp-Hodgkin Syndrome. Hay-Wells

Syndrome is probably the same. Mutation in the TP63 gene on chromosome

3q28. Autosomal dominant.

Tooth nail syndrome

Focal Dermal Hypoplasia (FDH) (also known as Goltz syndrome)

Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP)

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of ectodermal dysplasia depend on the structures

that are affected. These are often not apparent at birth and are

often only picked up during infancy or childhood.

Affected organ

Hair

Scalp and body hair may be thin, sparse, and light in colour

Hair may be coarse, excessively brittle, curly or even twisted

Nails

Fingernails and toenails may be thick, abnormally shaped, discoloured,

ridged, slow growing, or brittle

Sometimes nails may be absent

Cuticles may be prone to infection

Teeth

Abnormal tooth development resulting in missing teeth or growth

of teeth that are peg-shaped or pointed

Tooth enamel is also defective

Dental treatment is necessary and children as young as 2 years

may need dentures

Sweat glands

Eccrine sweat glands may be absent or sparse so that sweat glands

function abnormally or not at all

Without normal sweat production, the body cannot regulate temperature

properly

Children may experience recurrent high fever that may lead to

seizures and neurological problems

Overheating is a common problem, particularly in warmer climates

Other signs and symptoms include:

Lightly pigmented skin, in some cases red or brown pigment may

be present. Skin can be thick over the palms and soles and is

prone to cracking, bleeding and infection.

Skin may be dry and is prone to rashes and infection.

Dry eyes occur due to lack of tears. Cataracts and visual defects

may also occur.

Abnormal ear development may cause hearing problems.

Cleft palate/lip.

Missing fingers or toes (digits).

Respiratory infections due to lack of normal protective secretions

of the mouth and nose.

Foul smelling nasal discharge from chronic nasal infections.

Lack of breast development.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment

for ectodermal dysplasia. Management of the condition is by treating

the various symptoms. Patients often need to be treated by a team

of doctors and dentists, rather than a sole practitioner.

Patients with abnormal or no

sweat gland function should live in cooler climates or in places

with air conditioning at home, school and work. Cooling water

baths or sprays may be useful in maintaining a normal body temperature.

Artificial tears can be used to prevent damage to the cornea in

patients with defective tear production. Saline sprays can also

be helpful.

Saline irrigation of the nasal mucosa may help to remove purulent

debris and prevent infection.

Early dental evaluation and intervention is essential.

Surgical procedures such as repairing a cleft palate may lessen

facial deformities and improve speech.

Wigs may be worn to improve the appearance of patients with little

or no hair.

Most people with ectodermal

dysplasia can lead a full and productive life once they understand

how to manage their condition. Special attention must be paid

to children if sweating and mucous production abnormalities are

present. Recurrent high fevers may lead to seizures and neurological

problems.

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

(EDS)

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS)

is the name given to a group of inherited disorders caused by

a defect in connective tissue synthesis and structure. This leads

to fragile, sagging skin, and loose joints. fragile tissue and

blood vessels. EDS may occur in males and females of all races

and usually first appears in young adults.

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes

(EDS) are currently classified in a system of thirteen subtypes.

Each EDS subtype has a set of clinical criteria that help guide

diagnosis; a patient’s physical signs and symptoms will be

matched up to the major and minor criteria to identify the subtype

that is the most complete fit. There is substantial symptom overlap

between the EDS subtypes and the other connective tissue disorders

including hypermobility spectrum disorders, as well as a lot of

variability, so a definitive diagnosis for all the EDS subtypes—except

for hypermobile EDS (hEDS)—also calls for confirmation by

testing to identify the responsible variant for the gene affected

in each subtype.

Classical EDS (cEDS) - A final

diagnosis requires confirmation by molecular testing. More than

90% of those with cEDS have a heterozygous mutation in one of

the genes encoding type V collagen (COL5A1 and COL5A2). Rarely,

specific mutations in the genes encoding type I collagen can be

associated with the characteristics of cEDS. Classical EDS is

inherited in the autosomal dominant pattern.

Skin hyperextensibility and atrophic scarring; and

Generalized joint hypermobility (GJH).

Vascular EDS (vEDS) - Patients

with vEDS typically have a heterozygous mutation in the COL3A1

gene encoding type III collagen. Autosomal dominant.

Family history of vEDS with documented causative variant in COL3A1;

Arterial rupture at a young age;

Spontaneous sigmoid colon perforation in the absence of known

diverticular disease or other bowel pathology;

Uterine rupture during the third trimester in the absence of previous

C-section and/or severe peripartum perineum tears; and

Carotid-cavernous sinus fistula (CCSF) formation in the absence

of trauma.

A genetic defect causes reduced

amounts of collagen, disorganisation of collagen that is usually

organised into bundles, and alterations in the size and shape

of collagen. The type of EDS a patient has depends on how collagen

metabolism has been affected. For example vascular EDS is caused

by decreased or absent synthesis of type III collagen.

Skin hyperextensibility: it

is easy to pull the skin away from the body and once released

it retracts to its original state.

Skin fragility: the skin easily splits. Wounds heal very slowly

resulting in gaping fish-mouth or cigarette paper scars.

Epicanthic folds: skin folds between the eyes make the bridge

of the nose appear wide.

Molluscoid pseudotumours: small spongy lumps 2-3cm in diameter

over pressure points such as the knees and elbows.

Nodules: small, firm lumps just below the skin surface on the

arms and shins.

Hypermobility: joints bend more than usual. The fingers are most

often affected but all joints can be involved. The joints may

dislocate but can be popped back painlessly.

Bruising and haematomas may arise after trivial injuries.

Internal collagen defects: heart murmur (mitral valve prolapse)

and arterial/intestinal/uterine fragility or rupture (usually

associated with the Vascular Type).

scoliosis at birth and scleral fragility (associated with the

Kyphoscoliosis Type)

poor muscle tone (associated with the Arthrochalasia Type)

ELASTOSIS PERFORANS SERPIGINOSA (EPS)

This is a rare disorder in which

abnormal elastic tissue is being pushed out of the skin (a process

known as transepidermal elimination). It usually appears in early

childhood or young adulthood and males are more commonly affected.

Cause

- Part and parcel of other disorders

such as Ehler-Danlos syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, osteogenesis

imperfecta, pseudoxanthoma elasticum and Down syndrome.

- Drug induced, eg., due to

penicillamine, a drug used in the treatment of Wilson's disease

( a disorder of copper metabolism) and scleroderma.

Penicillamine interferes with the normal cross linking of elastic

tissue. The elastic tissue is therefore abnormal and the skin

tries to push it out of the skin.

- It is generally believed that

the abnormal elastic tissue in the dermis (inner skin) causes

irritation so the skin attempts to remove it through the epidermis

(outer skin).

- In drug-induced EPS due to

D-penicillamine (a drug used in the treatment of Wilson's disease),

abnormal elastic tissue is probably the result of penicillamine

inhibiting an enzyme responsible for the crosslinks within elastin.

However, in the case of non-drug induced EPS, the cause of abnormal

elastic tissue is unknown.

Symptoms

- Small red papules, grouped

in linear, annular (ring-like) or serpiginous (serpent-like)

patterns. The centre of these papules may contain a pit, which

is covered by a scaly plug.

- Usually there are no symptoms

but sometimes EPS can be itchy.

- Usually appears on the sides

of the neck, face and arms.

- Approximately 25 to 40 percent

of cases of EPS occur in association with genetic diseases such

as Ehler-Danlos syndrome, Marfan's syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta,

pseudoxanthoma elasticum and Down syndrome.

Outlook

- EPS can persist for several

years before spontaneously resolving but has a tendency to recur.

What you can do

- You should consult a doctor.

What the doctor may do

- Determine the cause and eliminate

it (e.g. penicillamine)

- Treatment is not necessary

but the following may be used - topical corticosteroids, topical

retinoids, cryosurgery, and electrodesiccation and curettage.

TOP

Elastomas or elastin naevi include:

Isolated elastomas

Buschke-Ollendorf syndrome

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa

Buschke-Ollendorf syndrome is a rare hereditary disorder where

there is an increased accumulation of elastin in the dermis (elastoma).

Lesions may be present at birth but more usually appear within

the first year of life. They are firm yellowish wrinkled nodules

often group together to form plaques. The abdomen, back, buttock,

thighs or arms are commonly affected. Other manifestations of

the syndrome appear with time and may include osteopoikilosis

(inherited bone disorder identified on X-Ray), eye disorders and

spinal problems. autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder

due to mutations in the LEMD3 gene (607844) on chromosome 12q14.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa

(EPS) is a perforating disorder. In this case, abnormal elastic

fibres are extruded through the epidermis. It presents in adolescence

and typically affects one or more sites on the face, neck and/or

arms. Groups of scaly papules are generally arranged in an arc

or ring shape. EPS is associated with other disorders of connective

tissue such as Marfan syndrome, Ehler Danlos syndrome, osteogenesis

imperfecta, pseudoxanthoma elasticum and Down syndrome.

Elephantiasis nostras

verrucosa (ENV)

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

(ENV) is a rare form of chronic lymphedema that causes progressive

cutaneous hypertrophy. It can lead to severe disfiguration of

body parts with gravity-dependent blood flow, especially the lower

extremities. Various factors can cause obstruction of the lymphatic

system and result in ENV. Clinically, ENV is characterized by

nonpitting edema and superimposed hyperkeratotic papulonodules

with a verrucose or cobblestone-like appearance. (Early-stage

lesions might exhibit pitting edema; late-stage lesions exhibit

nonpitting edema.) It needs to be differentiated from pretibial

myxedema, filariasis, lipedema, chromoblastomycosis, lipodermatosclerosis,

and venous stasis dermatitis (Table 1).1

edema and fibrosis of the skin.

Several conditions that block lymphatic drainage can induce lymphedema,

including neoplasms, trauma, radiation treatment, congestive heart

failure,1 obesity, hypothyroidism,6 chronic venous stasis,2 and

filarial infection.

The pathogenesis of ENV is still

unclear. It is conceivable that first the lymphatic channels are

damaged and blocked due to one or more of the above-mentioned

conditions, and excessive protein-rich fluid accumulates in the

dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Second, the protein-rich fluid

decreases oxygen tension and might decrease the immunity of the

skin. Third, poor immunity increases the skin’s susceptibility

to infection by micro-organisms. Finally, there is swelling, fibrosis,

and disfiguration of the affected areas.4 Hence, a vicious cycle

begins, as the underlying conditions predispose the skin to microbial

infections.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

is commonly observed in gravity-dependent parts of the body, especially

in the lower extremities. In addition, other sites including the

upper extremities, abdomen, buttocks, face, or scrotum might be

involved.7–9 Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa usually begins

at the dorsal aspect of the foot and then progresses to the proximal

parts of the limbs. In the beginning, the lesion presents as mild

and persistent pitting edema. Later, the affected area loses its

elasticity and eventually has a hypertrophic, verrucose, cobblestone-like

appearance. During the physical examination, observation of the

Kaposi-Stemmer sign—inability to pinch the dorsal aspect

of skin at the base of the second toe5—is characteristic

of lymphedema. This phenomenon is attributed to skin thickening

caused by lymphedema.

Although the clinical presentation

is distinct, other diseases such as venous stasis dermatitis,

filariasis, lipedema, chromoblastomycosis, lipodermatosclerosis,

and pretibial myxedema should be clearly differentiated from ENV

(Table 1).1–5

The diagnosis of ENV is mainly

based on patient history, physical examination, and typical cutaneous

lesions. To identify causes of secondary lymphedema, skin biopsy

and imaging techniques including computed tomography, magnetic

resonance imaging, lymphangiography, and lymphoscintigraphy can

be necessary.

In the management of ENV, it

is crucial to treat the underlying causes. Lymphostasis can be

managed conservatively using medical bandages, compression stockings,

and mechanical massages. Elastic bandage compression is reported

to be an effective treatment.10 Diuretics and systemic antibiotics

might be needed to reduce edema and control infection. In addition,

hyperkeratotic plaques can be treated with topical keratolytics

or systemic retinoids.1 Owing to the teratogenicity of systemic

retinoids, it is important to provide contraception to female

patients before treatment. Patients should also receive careful

monitoring of serum lipids and liver function. Surgical intervention

can be considered in recalcitrant cases when the response to medical

treatment is poor.11 However, unsatisfactory outcomes are common

in the management of advanced stages of ENV.

Enlarged pores

Enlarged pores are depressions

in the facial skin surface that contain one or more openings to

the ducts carrying sweat and oil from their respective eccrine

glands and sebaceous glands.

Enlarged pores can be seen at

all ages and in all ethnic groups. Certain ethnic groups may have

larger pores, particularly those of African and Indian ancestry.

Pores often appear larger with age.

Factors that may lead to enlarged

pores include:

Increased sebum production

Hair follicle size

Use of comedogenic products

Loss of skin elasticity with age

Sun damage.

Acne is associated with enlarged pores — when sometimes open

comedones (blackheads) can be seen within a pore. Inflammatory

acne may cause enlarged pores through weakening sebaceous gland

and hair follicle openings, making them more prone to blockage.

Treatments that focus on preventing

and shrinking large pores are not very effective. They include:

Avoidance of skin creams that

induce blackheads and whiteheads

Weight loss (which is reported to reduce sebum production)

Chemical peels

Topical nicotinamide

Plant-derived copper chlorophyllin complexes

L-carnitine

Topical retinoids.

Oral treatments that are used for acne may also help. These include:

Combined oral contraceptives

Spironolactone

Isotretinoin.

Physical treatments targeting

the sebaceous glands may help enlarged pores. These include:

Laser treatment

Radiofrequency microneedling (skin needling).

Eosinophilic cellulitis

(Wells syndrome)

What is Wells syndrome?

Wells syndrome is a rare condition

of unknown cause. It is also called ‘eosinophilic cellulitis’.

What does Wells syndrome look

like?

Typically the rash is preceded

by itching or burning skin and consists of markedly swollen nodules

and plaques (lumps) with prominent borders. The patches are usually

bright red at first, frequently looking like cellulitis, then

fade over four to eight weeks, leaving green, grey or brown patches.

They can blister. The rash most commonly occurs on the limbs,

but may also affect the trunk.

The patient often feels very

tired and has a fever in approximately 25% of cases.

Wells syndrome

Wells syndrome

Investigations

A blood count may reveal increased

numbers of white blood cells called eosinophils – these are

often associated with allergy or insect bites.

The diagnosis of Wells syndrome

can be established by a skin biopsy finding of typical histopathological

features with many eosinophils and characteristic ‘flame

figures’. However, flame figures are not diagnostic of Wells

syndrome and can be seen in other conditions that have increased

numbers of eosinophils.

An important part of the management

of patients with Wells syndrome is to exclude underlying causes

such as parasitic disoders (e.g. a worm infestation) or an allergic

contact dermatitis with the help of the appropriate tests.

Treatment

Oral corticosteroid treatment

with prednisone can lead to a dramatic improvement within days

and the course is typically tapered over one month. Other treatments

include minocycline, dapsone, griseofulvin, ciclosporin and oral

antihistamines.

Mild cases may respond to topical

steroid therapy alone.

eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a

rare scleroderma-like disorder characterised by inflammation,

swelling and thickening of the skin and fascia (fibrous tissue

that separates different layers of tissues under the skin). It

affects the forearms, the upper arms, the lower legs, the thighs,

and the trunk (in order of decreasing frequency). The disease

is considered by some to be a deep variant of the skin condition,

morphoea.

Eosinophilic fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis

What causes eosinophilic fasciitis and who gets it?

The cause of eosinophilic fasciitis

is unknown but it may have something to do with abnormal immune

responses as hypergammaglobulinaemia and antinuclear antibodies

are present. In addition, toxic, environmental, or drug exposures

have been implicated.

It affects females and males,

children and adults, with most cases occurring between the ages

of 30 and 60 years.

What are the clinical features

of eosinophilic fasciitis?

Patients usually present suddenly

with painful, tender, swollen and red extremities. Within weeks

to months patients develop stiffness and affected skin becomes

indurated, creating a characteristic orange-peel appearance over

the surfaces of the extremities. In severely affected areas, the

skin and the subcutaneous tissue are bound tightly to the underlying

muscle. This creates a woody-type appearance.

In 50% of cases, the disease

is precipitated by an episode of strenuous physical exercise or

activity. Other signs and symptoms that may be present include:

Malaise, weakness, fever and

weight loss

Joint contractures of the elbows, wrists, ankles, knees and shoulders

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Inflammatory arthritis

How is eosinophilic fasciitis diagnosed?

Laboratory studies in early

active disease show eosinophilia, elevated ESR and polyclonal

immunoglobulin G. However, full thickness skin biopsy that includes

the dermis, subcutaneous fat and fascia is necessary to confirm

a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis, which has specific pathological

features.

What is the treatment for eosinophilic

fasciitis?

Treatment of eosinophilic fasciitis

is directed at preventing tissue inflammation. Oral corticosteroids

are the mainstay of treatment, with most patients responding well

to moderate-to-high doses of corticosteroids particularly if started

early in the course of the disease. Continued low doses may be

required for 2-5 years. In some cases, the disease may resolve

spontaneously.

Other drugs that may be used

in conjunction with corticosteroids include:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

agents (NSAIDs)

Hydroxychloroquine

Colchicine

Cimetidine

Azathioprine

Cyclosporine

Cyclophosphamide

Methotrexate

A physiotherapist is also important in the overall management

of eosinophilic fasciitis to prevent and treat joint contractures.

Eosinophilic folliculitis

Eosinophilic folliculitis is

a recurrent skin disorder of unknown cause. It is also known as

"eosinophilic pustular folliculitis" or "Ofuji

disease". Skin biopsies of this disorder find eosinophils

(a type of immune cell) around hair follicles – hence its

name.

There are several variants of

eosinophilic folliculitis.

All of them present with itchy

papules (bumps) or pustules. Eosinophilic folliculitis is rare

and more often affects males than females. Variants include:

Classic type – this occurs

most commonly in Japan

Eosinophilic folliculitis associated with advanced Human Immunodeficiency

Virus (HIV) infection

Infantile eosinophilic folliculitis

Cancer-associated eosinophilic folliculitis

Medication-associated eosinophilic folliculitis

What does eosinophilic folliculitis look like?

Eosinophilic folliculitis presents

with red or skin-coloured dome shaped papules (bumps) and pustules.

It may look rather like acne or other forms of folliculitis. The

papules mostly appear on the face, scalp, neck and trunk and may

persist for weeks or months. Less commonly, urticarial lesions

are seen (these are larger red irritable wheal-like patches similar

to urticaria). Palms and soles may rarely develop similar papules

and pustules, but in such cases the condition should not be called

"folliculitis" as there are no follicles in these areas.

Longstanding cases may develop

dermatitis or a form of prurigo, presumably because of the itching

and scratching.

Eosinophilic folliculitis of

HIV

Eosinophilic folliculitisEosinophilic folliculitisEosinophilic

folliculitisEosinophilic folliculitis

How is eosinophilic folliculitis diagnosed?

Skin biopsy reveals eosinophils

under the skin surface and around the hair follicles and sebaceous

glands. In many cases blood tests show a mild rise in eosinophil

cells and immunoglobulin-E (IgE), and reduced IgG and IgA levels.

Eosinophilic folliculitis is

often a feature of immunodeficiency. Eosinophilic folliculitis

associated with HIV infection presents when levels of CD4 lymphocyte

cells drop below 300 cells/mm3, a level at which there is an increased

risk of a secondary opportunistic infection. Cases of eosinophilic

folliculitis have also reported after bone marrow transplantation

before the immune system is back to normal functioning, and in

some individuals with inherited immune deficiencies.

What is the cause of eosinophilic

folliculitis of HIV?

The cause of eosinophilic folliculitis

of HIV is not known. Immunodeficiency appears to lead to increased

risk of allergic-type skin diseases. There is no proof that bacterial,

fungal or viral secondary infection is the cause, although some

researchers have postulated overgrowth of malassezia or demodex

(the hair follicle mite) might be involved. Another theory is

that there is a change in the immune system causing eosinophils

to attack the sebum (oils produced in the skin) of sebaceous gland

cells.

What is the treatment for eosinophilic

folliculitis?

In patients with HIV, eosinophilic

folliculitis is likely to improve or resolve with HAART (Highly

Active Anti-Retroviral Treatment), as CD4 cell counts rise above

250/mm3.

Other treatments that may be

effective include:

Indomethacin and other nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs are reported effective in up to 70% of

cases of eosinophilic folliculitis

Dapsone

Tetracycline antibiotics

Other antibiotics including metronidazole

Phototherapy

Topical steroids

Calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus ointment

Oral antihistamines such as cetirizine

Colchicine

Itraconazole

Permethrin cream (topical insecticide)

Nicotine patches

Isotretinoin and acitretin.

EPHELIDES

Ephelides are freckles most

commonly seen in children with fair skins, especially those of

Celtic origin.

Cause

- Inherited tendency. It's been

found that caucasians with many ephilides have at least one copy

of a variant MC1R (melanocortin 1 receptor) gene, which is the

same variant that causes red hair. The MC1R gene is responsible

for producing a set of instructions to MC1R protein, which sits

on the surface of the melanocytes (melanin pigment producing

cells). When working properly, it turns pheomelanin into eumelanin,

the pigment responsible for hair colors other than red. In people

with numerous ephilides and red hair, the variant MC1R gene does

not work properly so melanin production switches to generating

phaemelanin by default. A different variant may be responsible

for ephilides in non-caucasians.

Symptoms

- Small light brown or tan spots

on the sun-exposed skin, especially the cheeks, nose, shoulders

and the upper back.

- They are not present at birth

and appear later in childhood, with sun-exposure.

- Ephilides are more common

in people with fair skin of any race. They occur in especially

large numbers in people with white skin that cannot tan (Fitzpatrick

skin phototype 1) and red hairs (Celtic ancestry).

- Freckles typically become

darker with sun exposure for example, during the summer and lighten

during the winter months.

|

Ephelides.

Click on

image for larger view |

What you can do

- Protect against the sun (see

sun protection).

- Consult a doctor for treatment

if the freckles bother you.

What the doctor may do

- Lighten with chemical

peels or liquid nitrogen aplications.

- Prescribe hydroquinone

containing lightening creams.

TOP

Epidermoid cyst

A cyst is a benign, round, dome-shaped

encapsulated lesion that contains fluid or semi-fluid material.

It may be firm or fluctuant and often distends the overlying skin.

There are several types of cyst. The most common are described

here.

What is a pseudocyst?

Cysts that are not surrounded

by a capsule are better known as pseudocysts. These commonly arise

in acne.

Who gets cysts?

Cysts are very common, affecting

at least 20% of adults. They may be present at birth or appear

later in life. They arise in all races. Most types of cyst are

more common in males than in females.

What causes cysts?

The cause of many cysts is unknown.

Epidermoid cysts are due to

proliferation of epidermal cells within dermis. Their origin is

the follicular infundibulum. Multiple epidermoid cysts may indicate

Gardner syndrome.

An epidermal inclusion cyst is a response to an injury. Skin is

tucked in to form a sac that is lined by normal epidermal cells

that continue to multiply, mature and form keratin.

The origin of a trichilemmal cyst is hair root sheath. Inheritance

is autosomal dominant (the affected gene is within short arm of

chromosome 3) or sporadic.

The origin of steatocystoma is the sebaceous duct within the hair

follicle. Steatocystoma multiplex is sometimes an autosomal dominantly

inherited disorder due to mutations localised to the keratin 17

(K17) gene, when it may be associated with pachyonychia congenita.

More often, steatocysts are sporadic, when these mutations are

not present.

The origin of the eruptive vellus hair cyst is follicular infundibulum.

It may be inherited an autosomal dominant disorder due to mutations

in keratin gene.

A dermoid cyst is a hamartoma, a developmental error.

The origin of a ganglion cyst is degeneration of the mucoid connective

tissue of a joint.

Occlusion of pilosebaceous units (hair follicles) or eccrine sweat

ducts leads to a build-up of secretions. This can present as milia.

Occlusion of the orifice of a mucous gland can lead to a fluid-filled

cyst in a mucous membrane (lip, vulva, vagina).

A milium is a pseudocyst due to failure to release keratin from

an adnexal structure. The origin of primary milium is infundibulum

of vellus hair follicle at the level of the sebaceous gland; a

tiny version of an epidermoid cyst. The origin of secondary milium

is a retention cyst within a vellus hair follicle, sebaceous duct,

sweat duct or epidermis.

Pseudocysts in acne are formed by occlusion of the follicle by

keratin and sebum.

What are the clinical features of cysts?

Epidermoid cyst

Epidermoid cysts occur on face,

neck, trunk or anywhere where there is little hair.

Most epidermoid cysts arise in adult life.

They are more than twice as common in men as in women.

They present as one or more flesh–coloured to yellowish,

adherent, firm, round nodules of variable size.

A central pore or punctum may be present.

Keratinous contents are soft, cheese-like and malodorous.

Scrotal and labial cysts are frequently multiple and may calcify.

Epidermoid cyst is also called follicular infundibular cyst, epidermal

cyst, keratin cyst.

Epidermoid cyst

CystCystGardner syndrome

Gardner syndrome

More images of epidermoid cysts ...

Trichilemmal cyst

90% of trichilemmal cysts occur

on scalp; otherwise face, neck, trunk, and extremities.

Most trichilemmal cysts arise in middle age.

In 70% of cases, trichilemmal cysts are multiple.

They presents as adherent, round or oval, firm nodules.

There is no punctum.

The keratinous content is firm, white and easily enucleated.

A trichilemmal cyst is also called pilar cyst.

Trichilemmal cyst

Pilar cystPilar cystsPilar cyst

More images of epidermoid cysts ...

Steatocystoma

A solitary steatocystoma is

known as steatocystoma simplex.

More often, there are multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)

on chest, upper arms, axillae and neck.

The cysts arise in the late teens and 20s due to the effect of

androgens, and persist lifelong.

They are freely moveable, smooth flesh to yellow colour papules

3–30 mm in diameter.

There is no central punctum.

Content of cyst is predominantly sebum.

Steatocystoma multiplex

SteatocystSteatocystoma multiplexSteatocystoma multiplex

Eruptive vellus hair cysts

Eruptive vellus hair cysts are

present in childhood if familial, and later if sporadic.

Multiple 2–3 mm papules develop over the sternum.

The cysts contain vellus hairs.

Dermoid cyst

A cutaneous dermoid cyst may

include skin, skin structures and sometimes teeth, cartilage and

bone.

Most dermoid cysts are found on face, neck, scalp; often around

eyelid, forehead and brow.

It is a thin-walled tumour that ranges from soft to hard in consistency.

The cyst is formed at birth but the patient may not present until

an adult.

Dermoid cysts

Dermoid cystDermoid cystDermoid cyst

Ganglion cyst

A ganglion cyst most often involves

scapholunate joint of dorsal wrist.

These arise in young to middle-aged adults.

They are 3 times more common in women than in men.

The cyst is a unilocular of multilocular firm swelling 2–4

cm in diameter that transilluminates.

Cyst contents are mainly hyaluranic acid, a golden-coloured goo.

Ganglion cyst

Ganglion cystGanglion cystGanglion cyst

Mucous/myxoid pseudocysts arise in older adults on distal phalanx

They arise from distal interphalangeal joint, associated with

osteoarthritis.

They often present as a longitudinal depression in the nail due

to compression on the proximal matrix.

Myxoid pseudocyst

Digital myxoid cystMyxoid cystDigital myxoid cyst

More images of digital myxoid pseudocysts ...

Labial mucous/myxoid cyst

A cyst in the lip may be due

to occlusion of the salivary duct

They are also called mucocoele.

It is a soft to firm firm, 5–15 mm diameter, semi-translucent

nodule.

Mucocoele of lip

Mucocoele of the lipMucocoeleMucocoele

Hidrocystoma

Hidrocystoma is a translucent

jelly-like cyst arising on an eyelid.

It is also known as cystadenoma, Moll gland cyst, and sudoriferous

cyst.

The common solitary translucent eyelid cyst is an apocrine hidrocystoma.

Multiple cysts on the lower eyelid are eccrine hidrocystomas.

Hidrocystoma of eyelid

HidrocystomaHidrocystomaHidrocystoma

More images of hidrocystoma of eyelid ...

Milium/milia

Milia are 1–2 mm superficial

white dome-shaped papules containing keratin

Primary milia arise in neonates (50%), adolescents and adults;

they are rarely familial and sometimes eruptive.

Primary milia occur on eyelids, cheeks, nose, mucosa (Epstein

pearls) and palate (Bohn nodules) in babies; and eyelids, cheeks

and nose of older children and adults.

Transverse primary milia are sometimes noted across nasal groove

or around areola.

In milia en plaque, multiple milia arise on an erythematous plaque

on face, chin or ears.

Secondary milia arise at the site of epidermal repair after blistering

or injury, eg epidermolysis bullosa, bullous pemphigoid, porphyria

cutanea tarda, thermal burn, dermabrasion.

Secondary milia are reported as an adverse effect of topical steroids,

5-fluorouracil cream, vemurafenib and dovitinib.

Milia

MiliaEyelid miliaMilia

More images of milia ...

Vulval mucous cyst

A vulval mucous cyst is due

to occlusion of Bartholin or Skene duct.

It presents as a soft swelling in the introitus of vagina: a posterior

swelling is a Bartholin cyst and a periurethral swelling is a

Skene cyst.

Comedo and acne pseudocyst

Comedones are pseudocysts formed

by occlusion of follicle by keratin and sebum.

The open comedo (whitehead) and closed comedo (blackhead) are

small, superficial papules typical of acne vulgaris

Solar comedones arise in sun-damaged skin and are associated with

smoking.

Large uninflamed pseudocysts accompany inflammatory nodules in

nodulocystic acne and hidradenitis suppurativa.

Comedones

Open comedones

Open comedones

Closed comedones

Closed comedones

Solar comedones

Solar comedones

Pseudocyst of auricle

Pseudocyst of auricle (external

ear) follows trauma.

Pseudocyst of auricle

Auricular pseudocyst

Complications of cysts

Rupture of a cyst

The contents of the cyst may

penetrate the capsular wall and irritate surrounding skin.

The area of tender, firm inflammation spreads beyond the encapsulated

cyst.

Sterile pus may be discharged.

Secondary infection

A ruptured cyst may infrequently

become secondarily infected by Staphylococcus aureus, forming

a furuncle (boil).

Pressure effect

A dermoid cyst can cause pressure

on underlying bony tissue.

A ganglion cyst can cause joint instability, weakness, limitation

of motion and may compress a nerve.

A digital mucous cyst may place pressure on the proximal matrix

and cause malformation of the nail.

Malignancy

Cutaneous cysts and pseudocysts

are non-proliferative benign lesions.

Nodulocystic basal cell carcinoma is a common skin cancer that

presents as a rounded nodule and may initially be mistaken for

a cyst, but steady enlargement, destruction of the epidermis with

ulceration and bleeding occur eventually.

Malignant proliferative trichilemmal cyst is actually a misnomer.

It is an extremely rare tumour.

How are cysts diagnosed?

Cysts are usually diagnosed

clinically as they have typical characteristics. When a cyst is

surgically removed, it should undergo histological examination.

The type of lining of the wall of cyst and the cyst contents help

the pathologist classify it.

Epidermoid cysts are lined with

stratified squamous epithelium that contains a granular layer.

Laminated keratin contents are noted inside the cyst. An inflammatory

response may be present in cysts that have ruptured.

Trichilemmal cysts have a palisaded peripheral layer without granular

layer. Contents are eosinophilic hair keratin. Older cysts may

exhibit calcification. The proliferating variety is considered

a tumour.

Steatocystoma has a folded cyst wall with prominent sebaceous

gland lobules.

Dermoid cyst contains fully mature elements of the skin including

fat, hairs, sebaceous glands, eccrine glands, and in 20%, apocrine

glands.

The lining of the wall of a ganglion cyst or digital mucous cyst

is collagen and fibrocytes. It contains hyalin material.

Hidrocystoma has a thin lining wall of eosinophilic bilaminar

cells.

What is the treatment for cysts?

Asymptomatic epidermoid cysts

do not need to be treated. In most cases, attempt to remove only

the contents of a cyst is followed by recurrence. If desired,

cysts may be fully excised. Recurrence is not uncommon, and re-excision

may be surgically challenging.

Inflamed cysts are sometimes

treated with:

Incision and drainage

Intralesional injection with triamcinolone

Oral antibiotics

Delayed excision biopsy

How can cysts be prevented?

Unknown.

What is the outlook for cysts?

Cysts generally persist unless

surgically removed.

EPIDERMAL

NAEVI

Epidermal naevi are developmental

abnormalities caused by an overgrowth of the epidermis (upper

layers of the skin). They appear at birth or during childhood,

usually in the first year of life. The abnormality arises from

a defect in the ectoderm. This is the outer layer of the embryo

that gives rise to epidermis and neural tissue. Epidermal nevus

is a clinical term for a family of skin lesions that involve the

outer portion of skin, the epidermis, and are distributed in a

linear and often swirled pattern. Overall, epidermal nevi are

not uncommon congenital malformations, occurring in 1-3 per 1000

births.

Cause

- There are two copies of every

gene, one derived from the individual's mother and the other

from their father. There are two populations of skin cells (a

situation referred to as mosaicism), containing either the mother

or the father's genes. The epidermal naevus is thought to the

product of the abnormal skin cell If one of these populations

is abnormal, an epidermal naevus developed. Luckily, epidermal

naevi very rarely affect more than one member of the family.

Mutations have been detected in FGFR3, PIK3CA and HRAS in epidermal

naevi. Epidermal naevi are distributed along the lines of Blashko.

These lines are the tracks taken by groups of genetically identical

cells in the developing embryo. Skin cells that have the active

abnormal gene spread out to form the epidermal naevus, whereas

the remaining skin cells form the other areas of apparently normal

skin. New research has found point mutations in keratin genes

that support this theory. The abnormal gene is found in the epidermal

naevus cells but not in the normal skin. The same keratin 1 and

keratin 10 gene abnormalities have been found in parents who

have epidermolytic epidermal naevus and in their offspring who

have bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma (a rare form of ichthyosis).

So the epidermolytic epidermal naevus is thought to be a mosaic

form of this type of ichthyosis.The ATP2A2 gene abnormality that

arises in Darier disease has been detected in the affected cells

of a patient with acantholytic epidermal naevus, so this type

may be a mosaic form of Darier disease. Linear porokeratosis

may be a mosaic form of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis.

- Epidermal naevi are believed

to be genetically ‘mosaic’, meaning that the mutation

causing the nevi are not found in other cells of the body. Mosaicism

arises when the genetic mutation occurs in one of the cells of

the early embryo sometime after conception; such mutations are

called ‘somatic’ mutations. This mutated cell, like

the other normal cells, continues to divide and gives rise to

mutated daughter cells that will populate a part of the body.

The linear patterning of the epidermal nevus reflects the movement

of the mutant daughter cells during fetal growth. These linear,

developmental patterns are termed the ‘lines of Blaschko’.

Many epidermal cells within these affected areas harbor the mutant

gene, while most or all cells from uninvolved areas do not. After

birth, the nevus “grows with the child”, although some

new areas of involvement and/or extension of the nevus to new

areas can occur.

- Symptoms

- Raised brown area with a rough

warty surface.

- Tendency to occur in lines

along the length of a limb.

The lesions may be single or multiple and are usually present

at birth. All epidermal nevi show some changes in texture which

can range from very rough, warty and spiny, and often darker

than the surrounding normal or uninvolved skin (verrucous epidermal

nevus), to red and scaly (inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal

nevus or ILVEN), to yellowish, rough and pebbly appearance due

to proliferation of oil- or ’sebaceous’ gland-like

structures (nevus sebaceous). If they are limited to the epidermal

linings of the hair follicles, they may appear like blackheads:

nevus comedonicus. Another related and relatively common entity,

the Becker’s nevus, is a form of epidermal nevus with a

somewhat velvety texture, mild to moderate hyperpigmentation

and coarser vellus hairs. It typically occurs on the trunk during

childhood or adolescence in a broader, patchy rather than linear

pattern. The term ‘nevus’ is also used for other birthmarks,

malformations and some benign growths, such as melanocytic nevi,

or ‘moles’.

What you can do

- You should consult a doctor.

What the doctor may do

- Destroy the area using electrosurgery or the

carbon dioxide laser.

- Excise the area with or without

grafting.

TOP

EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA (EB)

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is

a group of rare inherited disorders characterised by blistering

of the skin after minor trauma. Some forms of EB are mild with

few blisters but others may be more severe with many blisters

on the skin and even inside the body such as the mouth, oesophagus,

stomach, respiratory tract, bladder, and elsewhere.There several

types of epidermolysis bullosa.

Cause

Most cases of EB are inherited although less common, EB occurs

without a family history, in which case it is due to spontaneous

mutation. Inheritence may occur in 2 ways:

- Autosomal dominant where only

one parent need be affected and the offspring has a 50% chance

of inheriting the defect. In autosomal dominant EB, only one

abnormal gene is needed to express the disease.

- Autosomal recessive where

both parents have to be carriers and the offspring has a 25%

chance of inheriting the defect. In autosomal recessive EB, you

must have two EB genes (one from each parent) to have the disease.

If you only inherit one abnormal recessive gene, you will be

a carrier but will not express the disease.

Types of EB

There are many other subtypes of EB. The presentation and severity

of EB is affected by the specific genetic changes and can at

times be difficult to classify.

- Epidermolysis bullosa simplex

(EBS) of which there are 3 subtypes

- Localised EBS (Weber-Cockayne

type) - Blisters develop on hands and feet.

- Generalised EBS (Koebner type)

- Blisters appear all over the body but commonly on hands, feet

and extremities.

- Generalised severe EBS (Dowling

Meara type) - Blisters appear all over the body and may involve

the mouth, gastrointestinal and respiratory tract. May be fatal.

- Junctional epidermolysis bullosa

(JEB) of which there are 2 subtypes

- Generalised severe JEB (Herlitz

type) - Generalised and most severe form of JEB where

blisters appear all over the body and often involve mucous membranes

and internal organs. High risk of fatality, usually within the

first 1 - 2 years of life.

- Intermediate JEB (Non-Herlitz

type) - Generalised blistering and mucosal involvement present

at birth or soon after. Less risk of fatality and survivors improve

with age.

- Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa

(DEB) which may be of 3 subtypes

- Dominant generalised DEB and

it's variant Barts syndrome which is associated with aplasia

cutis

- Generalised severe recessive

(R) DEB (Hallopeau-Siemens type)

- Generalised intermediate RDEB

(Non-Hallopeau-Siemens type)

- Kindler syndrome

Who gets EB

Symptoms

- In mild types blisters appear

on the hands and feet and elbows and knees.

- In more severe cases, they

appear all over the body and healing causes fusion of digits,

contraction of joints, narrowing of oesophagus.

- In very severe forms, the

blisters are associated with may occur anywhere on the body but

most commonly at sites exposed to friction and minor trauma such

as the feet and hands and knees and elbows.

- Usually appear at or soon

after birth but in mild cases, it may not be noticed until the

child is older. Sometimes, mild cases may be mistaken as ordinary

friction induced blisters.

- In severe cases, the baby

is born with raw skin because the blisters were shed in the womb.

Complications

- Infection.

- Scarring.

- Fusion of digits (fingers

and toes),

- Contractures of joints.

- Problems feeding due to narrowing

of oesophagus.

- Death

Diagnosis

- Based of family history and

clinical signs.

- Skin biopsy of a newly induced

blister which undergoes immunofluorescence antigen mapping (IFM)

and/or transmission electron microscopy (EM).

- Genetic testing may be available

in some countries.

- What you can do

- You should consult a doctor.

- Protect the skin against trauma.

- What the doctor may do

- There is no cure for EB.

- Treatment is symptomatic,

the main aims being to protect the skin against trauma, promote

healing and prevent complications.

- Give genetic counseling.

- Treat the complications.

- Research in gene therapy and

cell-based therapy is continuing in an effort to improve the

quality of life.

TOP

erysipelas

- what is erysipelas?

- Erysipelas is a superficial

form of cellulitis, a potentially serious bacterial infection

affecting the skin.

- Erysipelas affects the upper

dermis and extends into the superficial cutaneous lymphatics.

It is also known as St. Anthony's fire, with reference to the

intense rash associated with it.

- Who gets erysipelas?

- Erysipelas most often affects

infants and the elderly, but can affect any age group. Risk factors

are similar to those for other forms of cellulitis. They may

include:

- Previous episode(s) of erysipelas

Breaks in the skin barrier due insect bites, ulcers and chronic

skin conditions such as psoriasis, athlete’s foot and eczema

Current or prior injury (eg trauma, surgical wounds, radiotherapy)

In newborns, exposure of the umblical cord and vaccination site

injury

Nasopharyngeal infection

Venous disease (eg gravitational eczema, leg ulceration) and/or

lymphoedema

Immune deficiency or compromise, such as

Diabetes

Alcoholism

Obesity

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Nephrotic syndrome

Pregnancy

What causes erysipelas?

- Unlike cellulitis, almost

all erysipelas is caused by Group A beta haemolytic streptococci

(Streptococcus pyogenes). Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin

resistant strains (MRSA),Streptococcus pneumoniae,Klebsiella

pneumoniae,Yersinia enterocolitica, andHaemophilus influenzae

have also been found to cause erysipelas.

- What are the clinical features

of erysipelas?

- Symptoms and signs of erysipelas

are usually abrupt in onset and often accompanied by fevers,

chills and shivering.

- Erysipelas predominantly affects

the skin of the lower limbs, but when it involves the face it

can have a characteristic butterfly distribution on the cheeks

and across the bridge of the nose.

- The affected skin has a very

sharp, raised border.

It is bright red, firm and swollen. It may be finely dimpled

(like an orange skin).

It may be blistered, and in severe cases may become necrotic.

Bleeding into the skin may cause purpura.

Cellulitis does not usually exhibit such marked swelling, but

shares other features with erysipelas, such as pain and increased

warmth of affected skin.

In infants, it often occurs in the umbilicus or diaper/napkin

region.

Bullous erysipelas can be due to co-infection with Staphylococcus

aureus (including MRSA).

Erysipelas

ErysipelasErysipelasErysipelasErysipelas

What are the complications of erysipelas?

- Erysipelas recurs in up to

one third of patients due to:

- Persistence of risk factors

Lymphatic damage (hence impaired drainage of toxins)

Complications are rare but can include:

- Abscess

Gangrene

Thrombophlebitis

Chronic leg swelling

Infections distant to the site of erysipelas:

Infective endocarditis (heart valves)

Septic arthritis

Bursitis

Tendonitis

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (a kidney condition affecting

children)

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (dangerous blood clots that can spread

to the brain)

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (rare)

How is erysipelas diagnosed?

- Erysipelas is usually diagnosed

by the characteristic rash. There is often a history of a relevant

injury. Tests may reveal:

- Raised white cell count

Raised C-reactive protein

Positive blood culture identifying the organism

MRI and CT are undertaken in case of deep infection.

- What is the treatment for

erysipelas?

- General

- Cold packs and analgesics

to relieve local discomfort

Elevation of an infected limb to reduce local swelling

Compression stockings

Wound care with saline dressings that are frequently changed

Antibiotics

- Oral or intravenous penicillin

is the antibiotic of first choice.

Erythromycin, roxithromycin or pristinamycin may be used in patients

with penicillin allergy.

Vancomycin is used for facial erysipelas caused by MRSA

Treatment is usually for 10–14 days

What is the outlook for erysipelas?

- While signs of general illness

resolve within a day or two, the skin changes may take some weeks

to resolve completely. No scarring occurs.

- Long term preventive treatment

with penicillin is often required for recurrent attacks of erysipelas.

- Erysipelas recurs in up to

one third of patients due to persistence of risk factors and

also because erysipelas itself can cause lymphatic damage (hence

impaired drainage of toxins) in involved skin which predisposes

to further attacks.

- If patients have recurrent

attacks, long term preventive treatment with penicillin may be

considered.

-

- erythema ab igne

- What is erythema ab igne?

- Erythema ab igne (EAI) is

a skin reaction caused by chronic exposure to infrared radiation

in the form of heat. It was once a common condition seen in the

elderly who stood or sat closely to open fires or electric space

heaters. Although the introduction of central heating has reduced

EAI of this type, it is still found in individuals exposed to

heat from other sources.

- What are the signs and symptoms

and who is at risk?

- Limited exposure to heat,

insufficient to cause a direct burn, causes a mild and transient

red rash resembling lacework or a fishing net. Prolonged and

repeated exposure causes a marked redness and colouring of the

skin (hyper- or hypo-pigmentation). The skin and underlying tissue

may start to thin (atrophy) and rarely sores may develop. Some

patients may complain of mild itchiness and a burning sensation.

- Erythema ab igne

Erythema ab igneErythema ab igneErythema ab igneErythema ab igne

Localised lesions seen today reflect the different sources of

heat that people may be exposed to. Examples include:

- Repeated application of hot

water bottles or heat pads to treat chronic pain, e.g. chronic

backache

Repeated exposure to car heaters or furniture with built-in heaters

Occupational hazard for silversmiths and jewellers (face exposed

to heat), bakers and chefs (arms)

What treatments are available?

- The source of chronic heat

exposure must be avoided. If the area is only mildly affected

with slight redness, the condition will resolve by itself over

several months. If the condition is severe and the skin pigmented

and atrophic, resolution is unlikely. In this case, there is

a possibility that squamous cell carcinomas may form. If there

is a persistent sore that doesn't heal or a growing lump within

the rash, a skin biopsy should be performed to rule out the possibility

of skin cancer. Abnormally pigmented skin may persist for years.

Treatment with topical tretinoin or laser may improve the appearance.

- erythema dyschromicum

perstans

-

- What is erythema dyschromicum

perstans?

- Erythema dyschromicum perstans

is also called ashy dermatosis (of Ramirez), because of its colour.

It is a benign skin condition characterised by well-circumscribed

round to oval or irregular patches on the face, neck and trunk

that are grey in colour. They may be symmetrical in distribution

or unilateral.

- Early lesions may be reddish

in colour, often with a more pronounced border, and they may

be somewhat elevated. However, this phase is not always observed.

- The patient is otherwise well

with no associated disease or blood test abnormality.

- Erythema dyschromicum perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstansErythema dyschromicum perstansErythema

dyschromicum perstans

Who gets erythema dyschromicum perstans?

- Erythema dyschromicum perstans

most often affects darker skinned patients, most frequently Latin

Americans and Indians. However it has also been reported in people

of lighter skin colour and various ethnicities.

- Erythema dyschromicum perstans

may occur at any age but it appears to be more frequent in young

adults. Women are affected more often than men.

- What causes erythema dyschromicum

perstans?

- The exact cause for the disease

remains unidentified. It is often classified as a variant of

lichen planus because of its histopathological features. Over

the years, theories have included:

- Genetic susceptibility

Toxic effects of chemicals such as ammonium nitrate or barium

sulphate

Whipworm infestation

Viral infections

Adverse effect of drugs and medications

What is the differential diagnosis?

- Several other skin conditions

may appear similar to erythema dyschromicum perstans because

they also result in discoloured skin patches.

- Lichen planus pigmentosus

(erythema dyschromicum perstans may be a variant of this disorder)

Multiple lesions of fixed drug eruption

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Urticaria pigmentosa

Incontinentia pigmenti

Pinta

Leprosy

How is it diagnosed?

- In some cases the clinical

picture may be classical enough to diagnose the condition. A

skin biopsy may need to be performed in other cases to aid diagnosis.

This may reveal minor vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer

in early lesions, and pigmentary incontinence with dermal melanophages

in more established patches.

- What is the treatment?

- Unfortunately erythema dyschromicum

perstans is rather resistant to currently available treatments.

It may persist unchanged for years although some cases eventually

clear up by themselves.

- Treatments that may help improve

the appearance include:

- Topical steroids

Exposure to ultraviolet radiation

Pigment lasers e.g., Q-switched ruby laser

Chemical peels

The most successful systemic treatment has been clofazimine.

Dapsone, griseofulvin, hydroxychloroquine, isoniazid and corticosteroids

have been used successfully in a few cases.

-

- Erythema elevatum

diutinum (EED)

-

- Erythema elevatum diutinum

(EED) is a rare type of necrotising vasculitis that is characterised

by red, purple, brown or yellow papules (raised spot), plaques,

or nodules, found on the backs of the hands, other extensor surfaces

overlying joints, and on the buttocks.

- Erythema elevatum diutinum

Erythema elevatum diutinumErythema elevatum diutinumErythema

elevatum diutinum

Who gets erythema elevatum diutinum?

- EED may occur in any age group,

but patients are typically between 30 and 60 years old. It occurs

equally in men and women.

- What is the cause of erythema

elevatum diutinum?

- EED is classified as a small

vessel vasculitis. The cause of EED is not yet defined, but it

has been associated with the following conditions:

- Granuloma faciale

Recurrent bacterial infections (especially streptococci)

Viral infections (including hepatitis B and HIV)

Haematological diseases

Rheumatological diseases

What are the clinical features of erythema elevatum diutinum?

- Lesions usually start as papules

or nodules on the backs of the hands.

Other extensor surfaces affected include the knees, elbows, wrists,

ankles, fingers and toes. Buttocks, trunk, forearms, legs, palms

and soles may also be affected.

Lesions occurring on the face are indistinguishable from granuloma

faciale.

Lesions usually appear symmetrically.

Colour of lesions progress over time from yellow or pinkish to

red, purple or brown.

Lesions may enlarge during the day and go back to original size

overnight.

Rarely, blisters and ulcers may form.

Lesions usually feel firm and freely movable over the underlying

tissue.

EED can be symptomless or painful, or cause an itching or burning

sensation.

Symptoms can worsen after exposure to cold.

Arthralgia may be present.

How is erythema elevatum diutinum diagnosed?

- Several tests are available

to establish a diagnosis of EED.

- Skin biopsy (most important);

it shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Direct immunofluorescence

What is the treatment for erythema elevatum diutinum?

- EED is a chronic and progressive

skin disease that may last as long as 25 years. However, in some

cases after evolving over a 5-10 year period it may spontaneously

clear.

- Medication can be used to

limit progression of the disease.

- Dapsone is considered the

drug of choice for EED, mainly because of its rapid onset of

action and clinical experience has shown good responses. However,

lesions promptly recur following withdrawal of the drug.

- Other drugs that have been

occasionally reported to be effective include:

- Niacinamide

Colchicine

Hydroxychloroquine

Clofazimine

Cyclophosphamide.

Oral corticosteroids are generally ineffective.

- What is the outcome for erythema

elevatum diutinum?

- EED generally persists for

months, years or decades. It often recurs after apparently successful

treatment.

-

-

- Erythema induratum

(Bazin disease)

- Erythema induratum (Bazin

disease) presents as recurring nodules or lumps on the back of

the legs (mostly women) that may ulcerate and scar. It is a type

of nodular vasculitis

-

- Erythema infectiosum

-

- Erythema infectiosum is a

common childhood infection causing a slapped cheek appearance

and a rash. It is also known as fifth disease and human erythrovirus

infection.

- What is the cause of erythema

infectiosum?

- Erythema infectiosum is caused

by an erythrovirus, EVB19 or Parvovirus B19. It is a single-stranded

DNA virus that targets red cells in the bone marrow. It spreads

via respiratory droplets, and has an incubation period of 7–10

days.

- Who gets erythema infectiosum?

- Erythema infectiosum most

commonly affects young children and often occurs in several members

of the family or school class. Thirty percent of infected individuals

have no symptoms. It can also affect adults that have not been

previously exposed to the virus.

- Erythema infectiosum

Fifth diseaseFifth diseaseFifth disease

More images of erythema infectiosum ...

- What are the symptoms of erythema

infectiosum?

- Parvovirus B19 infection causes

nonspecific viral symptoms such as mild fever and headache at

first. The rash, erythema infectiosum, appears a few days later

with firm red cheeks, which feel burning hot. This lasts 2 to

4 days, and is followed by a pink rash on the limbs and sometimes

the trunk. This develops a lace-like or network pattern.

- Although most prominent in

the first few days, the rash can persist for up to six weeks

at least intermittently, and is most obvious when warm.

- Complications of erythema

infectiosum

- Although usually a mild childhood

condition, erythrovirus B19 infection can result in complications.

These include:

- Polyarthropathy in infected

adults (painful, swollen joints)

Aplastic crisis or potentially dangerous low blood cell count

in patients with haemolytic blood disorders such as autoimmune

haemolytic anaemia and sickle cell disease

Spontaneous abortion, intrauterine death (9%) or hydrops fetalis

in 3% of the offspring of infected pregnant women. This can occur

if erythema infectiosum occurs in the first half of pregnancy.

Parvovirus B19 does not cause congenital malformations. As the

risk of an adverse outcome is low, the infection is not routinely

screened for in pregnancy

Chronic parvovirus infection in immunodeficient patients, such

as organ transplant recipients, causing erythropoietin-resistant

anaemia, proteinuria, and glomerulosclerosis in a renal allograft

Rarely, encephalitis, hepatitis, non-occlusive bowel infarction,

amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, myositis and heart disease

How is the diagnosis of erythema infectiosum made?

- In most cases, erythema infectiosum

is a clinical diagnosis in a child with characteristic slapped

cheek and lacy rash. Parvovirus can cause other rashes such as

a papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome. The diagnosis can

be confirmed by blood tests.

- Parvovirus serology: IgG,

IgM. This test is reported in about 7 days.

Parvovirus PCR is more sensitive. This test is reported in about

3 days.

In situ hybridisation or immunohistochemistry on biopsy specimens

If the child is unwell, or has haemolytic anaemia, a full blood

count should be performed. Ultrasound examination and Doppler

examination of at-risk pregancies can detect hydrops fetalis.

- Treatment of erythema infectiosum

- Erythema infectiosum is not

generally a serious condition. There is no specific treatment.

Affected children may remain at school, as the infectious stage

or viraemia occurs before the rash is evident.

- The application of an ice-cold

flannel can relieve the discomfort of burning hot cheeks.

Red blood cell transfusions and immunoglobulin therapy can be

successful in chronic parvovirus infection or during an aplastic

crisis.

Hydrops fetalis due to parvovirus infection is treated by intrauterine

transfusion.

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Erythema multiforme is a hypersensitivity

reaction to infections or drugs or othetr trriggers characterised

by “target” lesions that are symmetrically distributed

with a propensity for the distal extremities. in the past SJS

and TEN were considered as the a severe form, erythema multiforme,

with its minimal mucous membrane involvement and less than 10

percent epidermal detachment, is now considered as a separate

entity.

Consensus classification

According to a consensus definition, Steven-Johnson syndrome was

separated from the erythema multiforme spectrum and added to toxic

epidermal necrolysis. [3] Essentially Steven-Johnson syndrome

and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are considered severity variants

of a single entity. The 2 spectra are now divided into the following:

(1) erythema multiforme consisting of erythema minor and major

and (2) Steven-Johnson syndrome / toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN).

The clinical descriptions are as follows:

Erythema multiforme minor - Typical targets or raised, edematous

papules distributed acrally

Erythema multiforme major - Typical targets or raised, edematous

papules distributed acrally with involvement of one or more mucous

membranes; epidermal detachment involves less than 10% of total

body surface area (TBSA).

SJS/TEN - Widespread blisters predominant on the trunk and face,

presenting with erythematous or pruritic macules and one or more

mucous membrane erosions; epidermal detachment is less than 10%